I was born in Bermondsey and grew up there in the 1950s and 60s. I was inspired to use it as the backdrop for my novels when I realized that the once tight knit community I grew up in had vanished forever.

You never know what you’ve got till it’s gone; so goes the saying, but I think that sometimes you can know what you’ve got just at the point of losing it. When they were in their seventies my parents were part of a reminiscence group called ‘Bermondsey Memories’ and one day a group of academics came to their house conducting a study about building ‘communities’ in the modern world. They were looking for answers in the history of Bermondsey: the village-like, working-class, riverside area in the heart of London. But all my parents could tell them were that times were hard in those days, growing up between the wars, and people naturally helped each other. Ironically, the very things that had potentially caused most misery in the lives of Bermondsey people: the poverty, poor housing, lack of health care, had proved to be the source of their community spirit. But when your birthplace becomes the subject of an academic study, you know it is fast fading into history and I wanted to capture that lost world before it was totally forgotten.

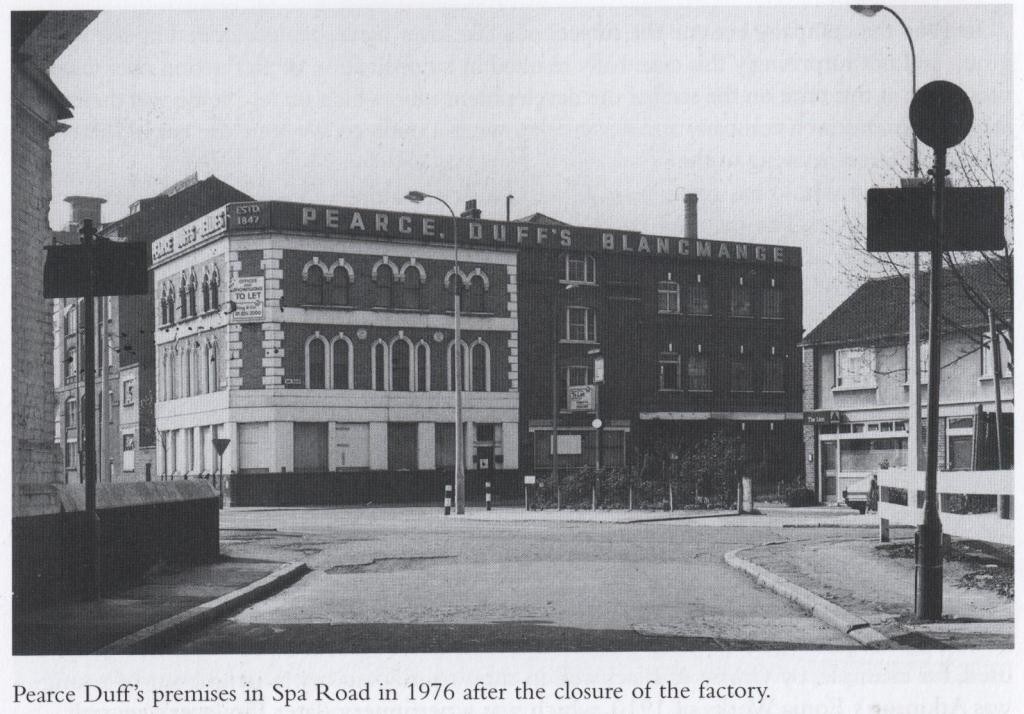

Although my books are works of fiction, I’ve drawn on many of my parents' and grandparents' stories of their lives in Bermondsey for inspiration. My debut novel Custard Tarts and Broken Hearts was largely inspired by my grandmother who started work as a powder packer in Pearce Duffs custard factory before World War One and worked there for most of her life. The Bermondsey women’s strike of 1911 gave me the starting point for the story, when I realized that my grandmother would have been one of the thousands of strikers who walked out of the factories, dressed in their Sunday best, one sweltering day in what became known as the ‘Summer of Unrest’. The ending was inspired by my grandfather’s experiences in the Royal Field Artillery during World War One. Although reticent about the war, he always said how deeply affected he’d been by the plight of the war horses he rode, and I’ve woven this into the novel’s conclusion. It seems fitting that the story of the ‘custard tarts’ and their men who marched away should have been published in the centenary year of the outbreak of the First World War.

Jam and Roses, my second novel, is set in the Dockhead area of Bermondsey, and I’ve been inspired by my mother’s stories of growing up in the largely Catholic, poor riverside community of docks, warehouses, food factories, slum courts and alleys, where the depth of poverty of its residents was equalled only by their generosity of spirit. Life was hard, but there were many inventive ways to soften that harshness. My heroine, Milly Colman, for instance, loves the yearly trip ‘down hopping’. She finds a freedom in the hop fields that allows her spirit to expand and her heart to soften. Again, I have drawn on many of my mother’s ‘hopping stories’ for this section of the book. As a child it was her only holiday and though the children were expected to work, it was an eagerly awaited escape to the country each year. Milly’s sister Elsie, is a sensitive soul, unsuited to the tough life she’s born into and she escapes to a fantasy world of talent competitions and ‘grottos’. I first heard about these childish constructions, using shells and bits of coloured paper or glass found on the Thames foreshore from my own aunt who remembered making them as a child in the twenties. Amy, the youngest sister, runs wild in the streets, and many of her street games are those I played myself: Run Outs, British Bulldog, Tin Tan Tobernopple - though the game goes under many names, Tin Can Copper or Tin Can Alley, among them!

But in all the personal stories of hardship I heard, whether it was of a beaten wife or a child incarcerated in an asylum, there was never a hint of self pity. There was always a sunny side. The ‘jam’ of hard graft in a jam factory was always offset by the ‘roses’. Which could take the form of a few weeks ‘down hopping, or a factory beano, or the literal roses planted in Bermondsey due to the selfless work of Ada Salter, who founded the Beautification Committee and filled Bermondsey with trees and flowers in the dark days of the depression.

The streets and buildings of Bermondsey I mention in my novels are for the most part real. Much of the area today is unrecognizable, as it was razed to the ground, firstly by Bermondsey Council’s ambitious slum clearances, then later by the Luftwaffe! In 1927, Bermondsey’s MP Dr Salter prophesied that when the next war inevitably came ‘Bermondsey will be an area of smashed buildings, wrecked factories, devastated houses, mangled corpses, and bodies of helpless men, women and children…’ Fourteen years later, the Blitz proved him tragically right. This was the backdrop for my third novel Gunner Girls and Fighter Boys, where I drew heavily on my father’s own war diaries of his time in the RAF in the far east and on his letters home to my mother, who was herself a gunner girl in the ATS.

Bourbon Creams and Tattered Dreams returns to nineteen-thirties, depression hit Bermondsey and to Matty Gilbie, a character from my first novel. She has found success on Broadway and in the talkies, but is forced to flee America and her mobster boyfriend, returning to Bermondsey with her dreams of screen stardom in tatters. There she exchanges tinsel town for biscuit town! The only place Matty can find work is Peek Frean’s biscuit factory, which occupied such a vast tract of land along the railway viaduct that it became known as ‘biscuit town’. Employing more than four thousand people, the women had to be single, were strictly supervised and wore caps like Thirties’ lady’s maids, which of course my heroine Matty hates, along with the smell of bourbon creams! This detail was inspired by a ninety-year old relative who still finds the smell of a custard cream can induce nausea seventy years after she last worked at Peeks. By the fifties, the headgear had become a white turban, and the ban on married women lifted, but very little had changed. My own mother joined the stream turbaned women who would supplement the family income by working the evening shift at Peeks, and the great perk for us children, was always the weekly bag of broken biscuits, sold cheap to workers! Needless to say, for a heroine as resourceful as Matty, biscuit town is not enough and she doesn’t intend to stay on the bourbon cream line for ever!

Hattie’s Home is set in the post-war period of austerity. In 1947 life was tough, with shortages of houses, food, coal, clothes, cigarettes and jobs. Railways, roads and industry were crippled and the weather didn’t help either. One of the worst winters in living memory gripped the country. Bermondsey was particularly hard hit by the war. Of its 19,500 dwellings, only a handful had escaped bomb damage and many of its factories and docks had been destroyed. I imagined my heroine returning to this wasteland after more than five years of fighting a war to save a home which, when she arrives, she finds destroyed. She reluctantly goes back to work at the Alaska Fur Factory - where my mother and aunts all used to work. I even did a stint there myself as teenager and well remember long, dull hours working on the bambeater! The bombsites of Bermondsey which form the back drop of the novel are also vivid in my memory, as, by the fifties, those stark places which had seen so much tragedy and loss were beginning to become adventure playgrounds.

In A Sister's Struggle, set in the 'hungry thirties', my young heroine struggles with poverty, family loyalties, her conscience and her loves. But the central question of the novel is: who will win the battle for Ruby Scully’s heart? Bermondsey during the nineteen thirties was a fascinating mix of mission field and battle field. From the soup kitchens of the South London Mission at the top of Tower Bridge Road to the little known ‘Battle of Bermondsey’ fought among the barricades of Long Lane, idealistic Ruby Scully, struggles to make a better life for herself, her family and friends. As she and a group of her young workmates at Crosse & Blackwell’s pickle factory fall variously in love with Methodism, Marx, Mosley and each other, it becomes clear that hearts and minds are the real battle field and it takes a terrible tragedy to reveal the truth behind each of their faiths and loves.

My latest novel, The Bermondsey Bookshop, is inspired by the real shop in Bermondsey Street, founded by visionary ex-actress, Ethel Gutman, in 1921. Her aim: ‘To bring books and the love of books into Bermondsey.’ Everything was designed to make the shop accessible to local working people, and my story follows Kate Goss who lives in a dark, freezing garret, bullied by her aunt and cousins after the death of her mother. She dreams of being rescued by her handsome, absent father, certain that he will come back a rich man. At seventeen, Kate is tough and hardened. When her aunt throws her out on to the streets, she finds a job as a cleaner in The Bermondsey Bookshop where long-held secrets are about to ensnare her in a web of lies and violence. But Kate is an unusually resilient girl and, for her, the orange door of The Bermondsey Bookshop becomes a portal to another world, where eventually she finds the key that unlocks both her past and her future.

Here are a few photographs of the locations mentioned in the novels, as they were at the time they appear in my books.

Listen to some of the songs featured in the books.

We Are The Bermondsey Girls

Poverty Street

Two Sweethearts

My Dear Old Dutch

Mother I Love You

If Those Lips Could Only Speak

Down Every Street

Dear Old Pals

Cruising Down The River

Call Round Any Old Time

(Members of the Bermondsey Memories Reminiscence Group, recorded by Teresa Tyrell in collaboration with the Horizon Radio Project 1991.)

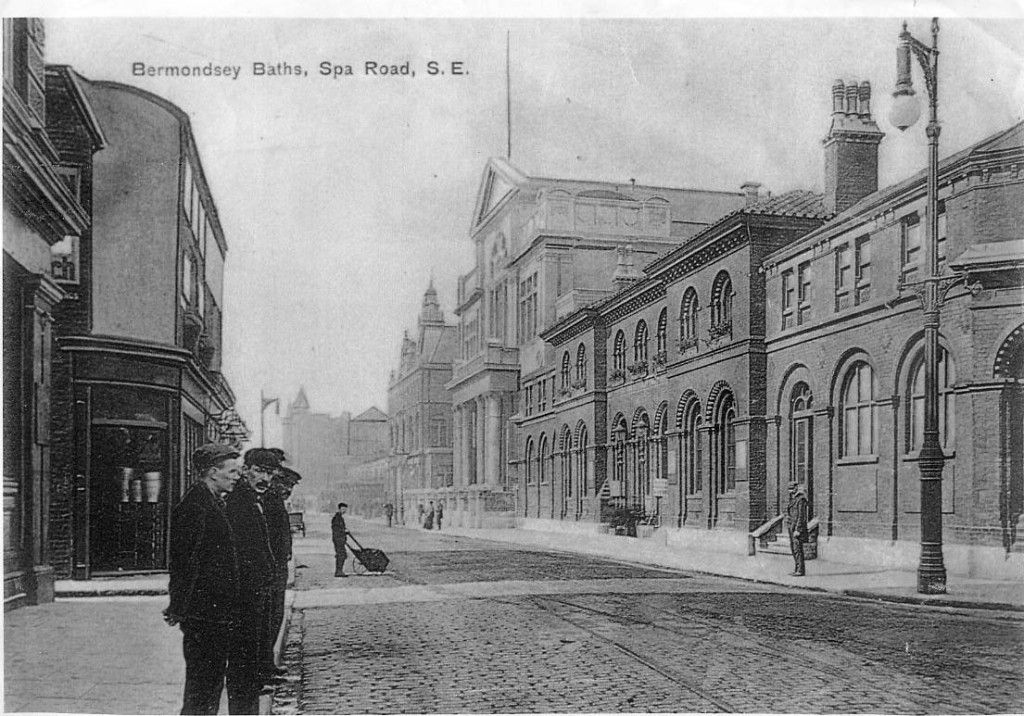

Spa Road, Bermondsey. 1906. The building with pillared entrance is the Town Hall.

Pearce Duffs custard factory, Spa Road, Bermondsey,

where Nellie Clark works in Custard Tarts and Broken Hearts.

To see more archive images and family photos which have inspired Custard Tarts and Broken Hearts - Click here

Arnold's Place, Dockhead, Bermondsey, where Milly Colman and her family live in Jam and Roses.

St. Saviour's dock, Bermondsey.1927. The 'Dockhead' in Jam and Roses.

Children leaving Dockhead Convent School , 1906.

This is the Colman sisters' school in Jam and Roses.

Surrey Docks ablaze following air raids in September 1940. The sight that May and Bill would have witnessed as they stood on Tower Bridge in Gunner Girls and Fighter Boys.

Bomb damage to Garner's and other leather factories in The Grange area of Bermondsey during the Blitz 1941. Garner's is where May and Bill worked in Gunner Girls and Fighter Boys.

Air raid shelter under Spa Road railway arch, Bermondsey in 1939. This is similar to the John Bull arch air raid shelter which features in Gunner Girls and Fighter Boys.

The ill fated John Bull Arch. First bombed in December 1941, this is the arch housing a large air raid shelter which features in Gunner Girls and Fighter Boys. This image shows crews repairing damage from a V2 rocket in October 1944. Ten days after repairs were completed it was hit by another V2 and completely destroyed.

To see more archive images and family photos which have inspired Custard Tarts and Broken Hearts - Click here

To see more archive images and family photos which have inspired Jam & Roses - Click here

To see more archive images and family photos which have inspired Gunner Girls and Fighter Boys - Click here

To see archive images which have inspired Bourbon Creams and Tattered Dreams - Click here

To see archive and family photos which have inspired Hattie's Home - Click here

To see archive images which have inspired A Sister's Struggle - Click here

To see archive images which have inspired The Bermondsey Bookshop - Click here